2026 Moons in Ojibwe

A Brief History of Our Language, The Moons & The Months

The Ojibwe language is ecologically embedded, functioning not merely as a system of communication but as a repository of traditional ecological knowledge. This means it is shaped by seasonal cycles and relationships with the land or specific region rather than by fixed systems of time like the Gregorian calendar and that it tells us stories. Because of this, Ojibwe speakers from different regions are often able to understand one another, while still using different words or expressions based on their local environments. These regional differences are especially important when learning about moons, similar to months in English. Over the last couple of weeks, learning the moons has become more of a research project than a straightforward language learning exercise.

One complexity that has required further research is that moon names are not simply vocabulary. They are tied to what is happening on the land during a particular period. Harvests, weather patterns, animal behavior and ecological change all inform how a moon is named and understood. As a result, the same moon may have different names and can occur at slightly different times depending on geography and seasonal conditions.

Another layer of complexity comes from the impacts of colonization. Colonization disrupted Ojibwe language transmission most severely through residential schools, which explicitly sought to remove Indigenous languages, as well as cultural practices and ways of understanding the world. These systems replaced Indigenous frameworks of time and relationship with British and European ones, including the Gregorian calendar. The impacts of this were numerous and devastating, but in regards to this subject, over time, this led to the re-interpretation of traditional teachings in many regions.

It is important to note that regional variation in Ojibwe language existed long before colonization. Colonization did not create dialectal differences, but it did interrupt how knowledge was passed on and often forced Indigenous systems of time to conform to British structures. This makes it difficult today to distinguish between pre-colonial practices and post-colonial adaptations, regardless of the method of learning. Moons vs months is where we see a clear impact.

Before colonization, Ojibwe communities named each full moon based on seasonal and ecological characteristics rather than fixed calendar months. One example is Manoominike-giizis, which translates to Ricing Moon. This moon corresponds to the period when wild rice is harvested, which typically occurs in late August into early September, depending on local conditions that year. The moon is named for what is happening in Northwestern Ontario, specifically Wabigoon Lake but also holds across the broader Great Lakes and Ontario rice region.

Another example of regional specificity comes from Wasauksing First Nation (near Parry Sound, north of Toronto), where the ninth moon, often aligned with August, is identified as Mdaamiin Giizis, or Corn Moon. In this southern region, corn agriculture was ecologically viable, making this moon name appropriate to local seasonal realities. This further illustrates how Ojibwe moon names reflect place-based relationships.

Many modern language resources identify only twelve months, aligning moon names with the Gregorian calendar. However, a lunar year does not fit neatly into a twelve-month structure. Some years contain twelve full moons, while others contain thirteen. In many Anishinaabe traditions, each full moon is named and observed as it occurs, without forcing it into a fixed monthly system. When a thirteenth moon appears, its timing varies from year to year, which means its name may vary as well.

This mismatch between lunar cycles and the Gregorian calendar helps explain why different Ojibwe sources sometimes contradict one another. The tension is not a failure of the language, but a result of trying to translate a land-based, relational system of time into a rigid colonial framework. Understanding this has reshaped how I approach learning the language. It is not only about words, but about re-learning how time itself is understood in relation to land and seasons.

I do not have direct access to Ojibwe speakers from my community at this point, so I’m learning from a mix of resources, primarily:

Survival Ojibwe: Learning Ojibwe in Thirty Lessons by Patricia M. Ningewance

Pocket Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe): A Phrasebook For Nearly All Occasions

DNFC (an App) through Ogoki Learning

My Personal Learning & Research Process

My process for learning the moons began with the DNFC app, which features recorded Ojibwe speakers from my community in Wabigoon saying the months aloud. I listened and wrote the words down as best I could based on what I was hearing, you’ll see that documented in the table below. The app, however, presents the language using Gregorian months rather than lunar cycles. This is frustrating for me because it seems to indicate the impact of colonization directly on my people, which leaves me with a feeling of loss and grief over what that means for our language. Since I have not spoken with anyone from my community about this, I cannot confirm that factually.

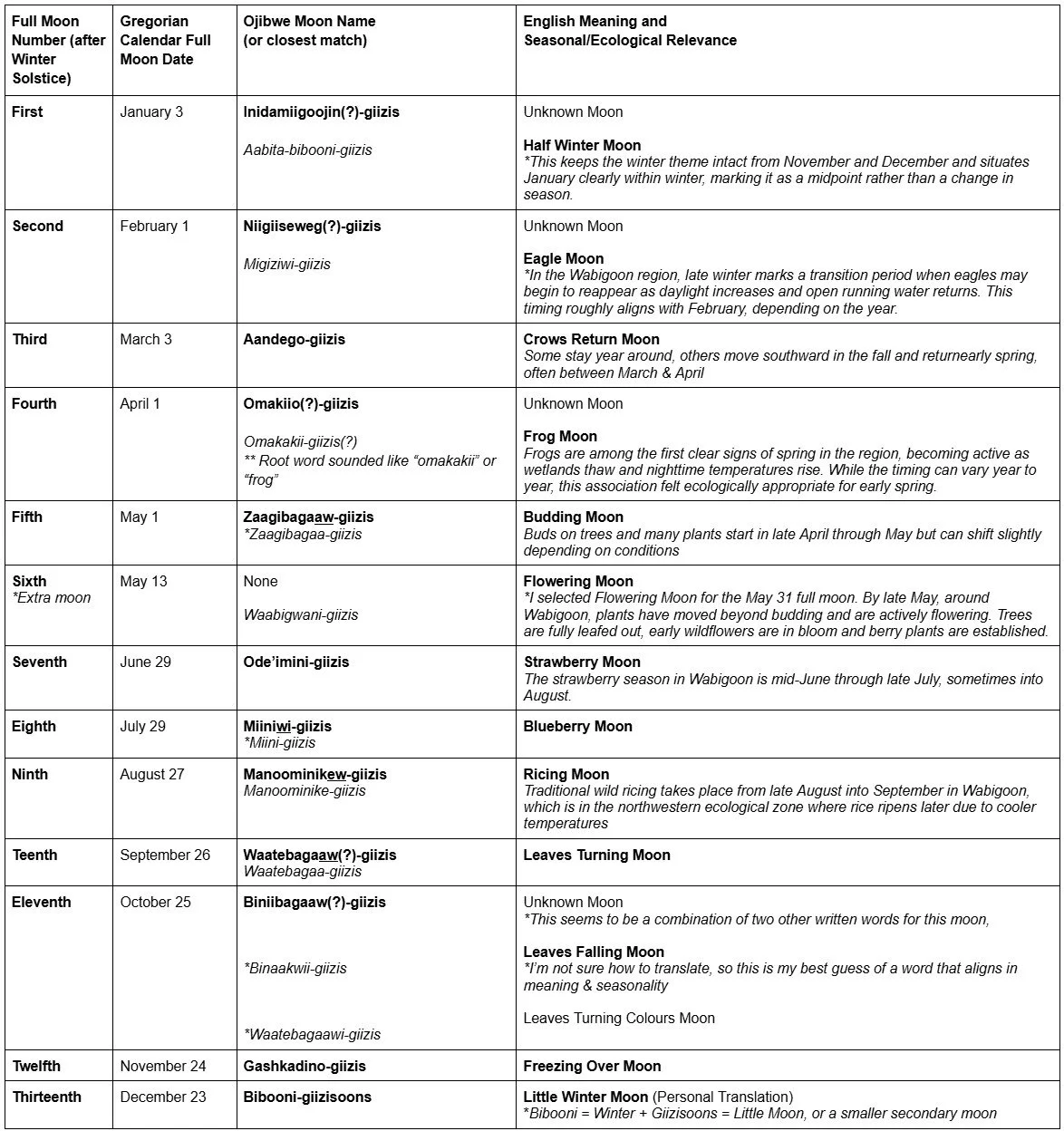

Here are my findings so far. This table reflects my own interpretation and I am still in the very early stages of learning. I also recognize that my approach may not be fully culturally rooted, it is weaved in the frameworks of both lunar cycles and Gregorian calendar moths. I am working with the information available to me and trying to make sense of it in the only way, the only way I currently know how.

Logic Breakdown

The Winter Solstice in 2025 fell on December 21. The last full moon before the solstice occurred on December 4, which means the first full moon after the Winter Solstice took place on January 3. Based on this, I began counting the moons from that point forward.

Table Column Explanations

Number of each full moon following the Winter Solstice

Corresponding Gregorian calendar date of the full moon

Moon name, as I understood it from the language app or similar-sounding references (I apologize for my spelling on the unknowns)

Translation of each moon name and regionally specific observations on ecological patterns

Note “Giizis” = Full Primary Moon or Month (different from if you’re talking about the moon)

Screenshot of my table of: Full Moons x Gregorian Dates x Ojibwe Names x English Meanings

Notes

If I could not fully understand a word, I did my best to type it as I heard it and added a question mark (?).

If I could not find a similar sounding reference from other sources, or if the sound and spelling did not align with what I heard in the DNFC app, I included common alternatives (*) that I feel are regionally appropriate, based on the seasonality and ecological characteristics of the time.

When possible, I also included the spelling used on a reference site (*) beneath the original transcription and underlined the variation in pronunciation.

There are many assumptions here, along with my own interpretations informed by research into the local ecology.

I did my best to create this reference for 2026 in a way that reflects what I understand may have been intended, including how the sixth (extra) moon, occurring on May 31, might have been named or understood. My hope is in the coming years it would help identify the variable moon

Other Notes on Research

I know it’s simple, but I’m very proud to share that I was able to translate “aandeg” to “crow” using the Ojibwe Survival Book. From there, I searched and found references to the Crow Returns Moon, I did something similar with Frog. This felt like a meaningful confirmation of the process!

I also tried searching “niigi” based on what I thought I heard in the pronunciation of February, and found that it can be a verb root meaning “to cause or make something grow or increase.” If we connect this to my assumptio of the intention being “Eagle Moon” in may indicate an increase in numbers of Eagles during this moon phase. This may be a completely superfluous connection, especially if my spelling is inaccurate based on what I was hearing.

References

Reference for sheet: https://ojibwe.net/projects/months-moons/ (Western Dialect)

Reference sheet for … https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/main-entry/omakakii-na

Other Resources

https://www.masteranylanguage.com/c/r/en/Ojibwe/MonthsOfYear

https://www.wakingupojibwe.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Giizisoon-Monthly-Birthday-Headers.pdf

Miigwetch

Thank you for joining me on my learning journey.

-Kai (Diindiisi)